Remote offshore installations, dusty mines, dirty sewers: environments made by people for people. Yet operating them is dangerous. The solution? The robotic dog from ANYbotics, which can carry out inspections autonomously.

Robotic Dog Can Carry Out Inspections Autonomously

Robotic Dog Can Carry Out Inspections Autonomously

Article from | maxon group

Fall down, get up again. Over and over again. How do I position my feet? How do I apply force? And how do I control my balance? When children are learning to walk, they feel their way into the movements over a period of weeks. Péter Fankhauser’s “baby” learns in a similar way – even though its legs consist of springs, sensors, and motors. He proudly reports: “ANYmal taught itself to climb stairs in a simulation. It took the robot only a few hours. The fantastic thing is that, unlike humans, thousands of ANYmals learn right along with it. That’s because we create virtual copies.” These copies are each given the general goal, such as to climb a flight of stairs as quickly as possible. Then disruptions are added, such as sensor noise or wind. The programs consequently learn to handle such situations independently. “Once the simulated learning processes reach an optimum level, we transfer the control to all the real robots,” Fankhauser says.

An engineer with a doctorate in robotics, he sits on a colorful lounge suite in the meeting room and speaks easily at lightning speed about the inspection robot. He developed it together with eight other founding members of ANYbotics, a spin-off of ETH Zurich college. The dog-like ANYmal, he says, can move autonomously – that is, without human control or wifi – in harsh industrial environments with no people present. What’s really exciting is that the environment does not have to be specially designed to suit robots, as is the case in large factories or warehouses. No, the four-legged helper can find its own way, especially in spaces made for humans. Fankhauser points us to YouTube videos where we can see the machine clambering up and down steep steel stairs, or taking forest walks over roots and gravel paths. It balances on narrow steel beams, crawls under trains, and makes its way safely across sausage-thick cable coils on the ground. ANYmal can easily wade through water, survive a sandstorm, and doesn’t slip even on a blanket of snow. We even see it running backwards to deliver chocolate bunnies door to door at rush hour on Easter. Such situations require the highest concentration even from humans.

Smiling robot

How does the robot do it? Is the programming particularly difficult? “No, it’s relatively simple,” our specialist assures us. We learn more during a tour in Zurich. The ANYbotics complex houses not only offices and meeting rooms, but also the company’s test center and production facility. When you enter, you notice that there’s something in the air. Maybe it’s the tingle you get when you’re making progress. The excitement of imminent change – when you feel you’re on the verge of a breakthrough, like you’re part of something big. People in jeans and T-shirts greet you enthusiastically in English. 21 nations are represented here, with 25 more employees than a year ago. New spaces have just been leased, and ANYbotics recently raised 20 million Swiss francs from investors. This money is being used to commercialize the latest ANYmal model, the D version. This will also bring a structural change: Currently, a small in-house team manufactures about one robot per week. From 2022, the inspection helper will be produced in higher volumes on an assembly line, by a partner in Switzerland.

But despite the upswing, ANYbotics has remained grounded. The startup vibe is still there. In the open-plan office, whiteboards hang with complicated formulas and diagrams, but every now and then a manga character, as if escaped from a comic, mingles among them. Plush animals dangle from desk lamps. In the kitchen, the winning artwork from the last team competition is on display, small framed oil paintings: ANYmal waving from the back of a unicorn, ANYmal crawling through the sea, ANYmal floating around in space. Right next to them, vast continents spread across the wall, covered with photos of customers from all over the world. In the midst of it all is the friendly-looking robot, running, sitting, waiting. “Even with the C prototype, we were concerned not only with the robot’s function, but also with the emotions it arouses by its appearance. We were able to position its eyes so they look friendly. They are the cooling vents of the robot. The depth camera forms its mouth. A small bevel makes it look like a lip, smiling. Little things like that help evoke positive associations,” Fankhauser says. The latest model has a completely different face because ANYmal D had to be made even more robust, for industrial use. Nevertheless, the successor model looks benevolent too. “We wanted to create a friendly, reliable, and useful robotic colleague who helps out. After all, it is supposed to supplement the human workforce. So it has to give the impression: I’m here to help you. Incidentally, this rules out military operations and police missions.”

Offshore, it braces the wind and weather: The new ANYmal D model crawls up a flight of steel stairs by itself.

It sees, smells, hears – and calls out

Routine inspection work is especially suitable for automation using ANYmal. The ANYbotics CEO goes through the numbers, to show that this quickly pays off: “Every day lost to repairs costs the operators of industrial plants several hundred thousand francs. So the machines have to run with as few problems as possible.” Currently, it’s mainly people who do inspection rounds. “That works well – at least if they know the plant and have experience. But it takes a lot of time and money, and sometimes it’s highly dangerous.” On offshore installations, in sewers, or in mines, people are exposed to high pressure, electricity, hazardous gases, toxic substances, dust, and dirt. Therefore, if a person wants to inspect the facilities, they sometimes have to be switched off first – and that costs money. Then there is the issue of transportation costs. “Specialized people have to be transported to the plants, but each helicopter trip can easily cost more than CHF 30 thousand.” Shaking his head, Fankhauser adds, “Sometimes a flight to a drilling platform is necessary just to flip a single switch.” In the offshore sector, ANYmal therefore pays for itself within a few weeks.

Of course, there is also the option of equipping the plants with sensors to detect abnormalities in operation. However, that too is complex and costs a lot of money. “Each sensor also measures only a small part of the whole system, and has to be replaced over time,” Fankhauser observes. The robot, by contrast, has the advantage that it is designed for a relatively long time – three years of continuous operation, in fact – and can perform many tasks at the same time. The robotic dog is strong enough to carry loads. With its cameras and detectors, it sees, smells, hears – and “calls out” warnings: it reads and passes on data from measuring devices. It takes thermal images, and performs acoustic measurements. It will notice and report if there is gas escaping, or if the hum of a machine or the vibration of a pump suddenly sounds different.

Powerful motors, fast learning time

But how does this device manage to move so safely through difficult terrain? How does it learn its way around? Fankhauser says, “One option is to take ANYmal with you to the site and show it what it has to do, like with a new employee. We accompany the robot with a joystick while it walks the path and creates a 3D map. An hour-long inspection tour of a plant normally takes half a day of learning time.” Alternatively, the robot has the even simpler option of learning virtually. This is possible if a digital model of the plant already exists.

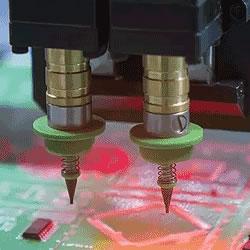

Orientation is achieved with sensors, while walking uses electric motors developed specially for the robot. “We realized that we needed our own drives, which had to be light, yet powerful. That’s why we entered into partnership with maxon. Our two companies are a very good cultural fit, and even work next door to each other now.” The robotic animal’s four limbs each contain three drives, meaning that a total of twelve actuators are installed in the ANYmal. They generate the walking motion, make the legs tilt out or back, and bend the knees. “Force control when walking on various surfaces is very important. When running, there is impact energy that has to be absorbed. To do that, we worked with maxon to develop a system with springs that mimics muscles and tendons.”

Solution and tricky challenges

In the ANYbotics test center, the tower of pizza boxes reaching almost to the ceiling bears witness to long days and short nights. Here, chairs, tables, and computers are grouped into a kind of spectator arena where data is collected and analyzed. On the stage, the fifty-kilogram robot works its way up and down stairs and over obstacles like bricks. Keeping a safe distance from the machine is mandatory for all employees. Safety certification is something that cost the company a lot of time and energy. “But now it’s done. We worked with external specialist laboratories to implement a strategy for electrical and mechanical safety.” Training customers in safety precautions also helps to reduce risks to a minimum.

After 90 minutes, ANYmal runs out of energy. It notices this on its own, stomps to its docking station, and sits down on it like a hen on an egg. Fankhauser explains: “You see videos on YouTube of this cool robot running up the stairs like a dog. But that’s only one small part of the solution.” The CEO points to the live screens of the computers. “You have to be clear about how the inspection data is going to get to the customer. We offer an end-to-end inspection solution. The software comes with an annual user license, including software updates and technical support.”

Some tricky challenges are still to be resolved: What if someone closes a door? ANYmal would be stuck standing in front of it. It is also not yet able to detect rust or cracks reliably. Also, it should really be able to do dangerous maintenance work right away by itself. The team in Zurich is now experimenting with gripper arms for this purpose. One thing’s for sure: this friendly robot is going to keep learning – and the pizza tower will keep growing.

The content & opinions in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily represent the views of RoboticsTomorrow

maxon group

maxon is a leading supplier of high-precision DC brush and brushless servo motors and drives. These motors range in size from 4 - 90 mm and are available up to 500 watts. We combine electric motors, gears and DC motor controls into high-precision, intelligent drive systems that can be custom-made to fit the specific needs of customer applications.

Other Articles

Multi-axis motion control drives pipe-based robots

Automate 2025 Q&A with maxon group

Understanding Torque and Speed in Electric Motors

More about maxon group

Featured Product